_JPG.jpg)

When Yu‑Hsuan drank ayahuasca in Peru, a sentence suddenly surfaced in her mind:

“Voices Emerging from the Blank—A Class on Reading and Writing Poetry.”

It felt like an oracle from within—a destined calling. Since then, she has continued traveling and writing, while also designing and teaching online courses that intertwine her cultural perceptions of the present moment, her sensory experiences from the road, and her inner landscapes. These elements are woven into close readings of poetry, analyses of cinema, and intuitive inquiries into art. These courses are more than a series of lectures — they are ongoing conversations of the spirit.

Below is a list of courses she has offered during her travels in recent years, as traces of her continued exploration of language, the body, and the world.

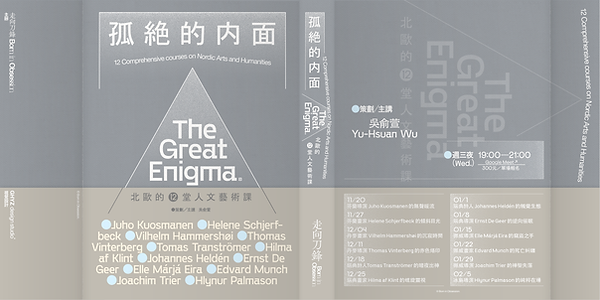

The Great Enigma — 12 Humanities and Arts Lessons from the Nordic North

The simplicity of Nordic art carries a quality of paring away — a tendency to strip things down to their essential spiritual state. In doing so, it allows human beings and nature to penetrate one another, sharing a single heartbeat. Inside and outside become a Möbius strip. Without a word, the surface already reveals mystery and depth. Look — that snow-covered mountain outside the window slowly turns into mist, becoming something eerily familiar: a solitary, austere interior.

◆ The Silent Warmth of Finnish Director Kuosmanen

I first came to know this director through The Happiest Day in the Life of Olli Mäki. His vision resonates with The Wounded Angel, the painting chosen by Finns as their national artwork: a closed-eyed angel holding a flower that only blooms in spring. It reflects a resilient and unadorned national spirit, capturing the essence of the Finnish word sisu: a silent perseverance, a resolve to move through stone.

◆ The Tilted Gaze of Finnish Painter Schjerfbeck

From her early self-portraits, Helene always looked toward the canvas with a tilted gaze—as if she weren’t staring at herself, but rather measuring or observing an object. Her face appears stripped of subjective presence, scrutinized from a distance—objectified, in order to enter the permissible structures of creation. In the end, she no longer judges herself harshly, but meets her own gaze with total disarmament.

◆ The Silent Time of Danish Painter Hammershøi

Hammershøi’s paintings are like miniature architectures of time, pure embodiments of time being captured. On the surface, they are radically simple, yet within the emptiness resides an ineffable tension. In these spaces of extreme quiet, we are compelled to bear the absence of narrative. Starting from Hammershøi’s compositional choices, I will explore how "silence" becomes a perceptual mode of time and existence.

◆ The Crimson Imprint of Danish Director Vinterberg

Vinterberg’s films always begin with the rupture of community—Another Round, The Hunt... Whether it's patriarchy, ethics, friendship, or desire, every relationship teeters on the brink of collapse. I will explore how Vinterberg employs rupture as an aesthetic method to examine the terrain of communal ethics, patriarchal structures, and the possibilities of healing after trauma.

◆ The Nocturnal Ecstasy of Swedish Poet Tranströmer

Tranströmer’s poetry can be seen as a linguistic sample of the Nordic spiritual landscape. His language is distilled and highly symbolic, revealing a tension between modernism and mysticism. I will explore how Tranströmer uses rhythm and imagery to bring language into a state of ecstasy. I will also share what kind of silence and abundance I encountered when I took a boat to his summer island.

◆ The Spiral Vision of Swedish Painter Hilma af Klint

Hilma once said, “These were not painted by me; they were painted by the spirits.” Hilma believed the spiral was the language of the cosmos, and that colors could summon vibrations of the spirit. I will begin with her sketches, symbolic notations, and The Paintings for the Temple to explore how Hilma used art as a form of mediumistic practice—unfolding a visual epistemology that transcends gender, materiality, and linear historiography.

◆ The Tactile Ecology of Swedish Poet Heldén

I will guide you through the dramatic worlds shaped by Icelandic artist Olafur Eliasson’s monumental installations, Swedish poet Johannes Heldén’s sensory poetics, Swedish artist Simon Stålenhag’s futuristic paintings, and Samoan poet Albert Wendt’s mythic verse. Their works construct immersive scenarios in which we feel ourselves not only as extensions of the world—but as active agents in the ongoing expansion of the world itself.

◆ The Reverse Hypnosis of Swedish Director Geer

I will examine Ernst De Geer’s first feature Hypnosen, alongside his 2018 graduation short Culture from the Norwegian Film School. How do his sharply layered scripts, meticulous editing, and razor-edge performances reflect a distinctly Scandinavian sensibility? Why is hypnosis a pathway to awakening? How does loss of control become a rite of passage—an absurd, narrow door to rupture and renewal?

◆ The Stealing Hand of Norwegian Sámi Filmmaker

I will explore how Arctic Sámi communities live in harmony with the natural world, responding to each decision with a deep sense of traditional wholeness—and how they confront the hostility of colonial human systems. Together, we’ll engage with Sámi artists’ prints, sculptures, films, and poems… and at the end of the journey, the 400 reindeer skulls I encountered at the National Museum of Norway will be waiting for you.

◆ The Death Entanglement of Norwegian Painter

Munch once wrote in his diary: “A man and a woman meet, slide toward each other, illuminated by the flame of love, and then disappear in their own directions.” In this session, I will delve into Munch’s life and the evolution of his paintings, sculptures, prints, and poetry. We will trace the shifts in his artistic methods and forms to understand how one artist navigated ruin—and found, through art, a way to survive despair.

◆ The Sacred Loss of Norwegian Director Trier

In this session, I will weave together Trier’s Reprise, Oslo, August 31st, Louder Than Bombs, Thelma, and The Worst Person in the World to explore his aesthetics of emotional honesty, temporal rupture, and existential longing. His films are not only portraits of individual loss but invitations to reflect on how we carry time, memory, and hope within the ruins of modern life.

◆ The Pure Presence of Icelandic Director Pálmason

From his debut feature Winter Brothers to A White, White Day and Godland, he portrays naked relationships in vast and isolated landscapes—relations that have no fragile corner to hide in. I will approach Pálmason’s films through the lens of formal aesthetics, exploring how he uses empty landscapes and the force of montage—creative conflict and poetic tension—to reveal the landscape of consciousness and the laws of life.

Echoes Through the Forest — A 1990s Asian Cinema Retrospective

In this series, I will explore the aesthetic grammar of ten films from 1990s Asian cinema. We’ll study how the camera moves, how the frame enacts its will, how editing links your gaze or slices through your illusions. What propels a narrative forward? At what moment does pacing shift or stall? How can a single monologue illuminate the folds of a person’s soul?

Each film will gradually unveil itself, teaching us how to read its own body. We will trace the barbs that stir our sensations—and ask: where do they tug? What do they reel in?

◆ Wong Kar-wai’s Days of Being Wild (1990)

What happened in 1990? Nelson Mandela was released from prison, a pivotal moment in South Africa’s anti-apartheid movement. Black rap music rose to the mainstream. The Wild Lily student movement swept through Taiwan. The Hubble Space Telescope was launched into orbit. The World Health Organization removed homosexuality from its list of mental disorders. Microsoft released Windows 3.0. Lee Teng-hui became the 8th President of Taiwan. A summit between Gorbachev and Bush in Washington signaled the symbolic end of the Cold War. East and West Germany were unified. And in Hong Kong, Days of Being Wild was born. Time resounds through this film—but what cuts even deeper than time is the fierce, unruly desire that burns through it. Let us revisit the film’s beautiful, melancholy faces, its breath-catching lines of dialogue, its close-ups that cling to sweat and the tremors beneath the skin—and the ambiguous space between memory and forgetting.

◆ Edward Yang’s A Brighter Summer Day (1991)

Edward Yang was born in 1947 and raised in Taipei. As a student at the prestigious Chien Kuo High School, he was fascinated by comic books depicting World War II. He once said that, in order to become the kind of “dutiful son” approved by Confucian tradition, he enrolled in the Department of Electrical Engineering at National Chiao Tung University. Later, he went to the United States to pursue graduate studies in engineering. After watching Werner Herzog’s Aguirre, the Wrath of God, he made a fateful decision: he wanted to become a filmmaker. At 33, he abandoned his career as a software designer in the U.S. and returned to Taiwan to devote himself to cinema. From his first feature That Day, on the Beach (1983) to The Terrorizers and A Brighter Summer Day, Yang used film as a means to actively reflect on and critique contemporary society, establishing himself as a central figure of the Taiwan New Cinema movement. But what, precisely, was “new” about this New Cinema? Beginning with the aesthetics of A Brighter Summer Day, I will examine how “society” gradually takes shape—becomes legible, even tangible—through the body and fate of a single adolescent.

◆ Ang Lee’s Pushing Hands (1992)

When Ang Lee was filming Lust, Caution, the process was so emotionally draining that he sought out his cinematic mentor. Upon seeing him, Lee collapsed onto Ingmar Bergman’s shoulder and wept. While Bergman’s films often center on the isolation and disintegration of the individual—a rupture where no redemption can be found in the relationship between self and others—Ang Lee, from his earliest works, never abandoned the search for a new ethical position for the individual within the conflicts of cultural relationships. His resistance is not expressed through rupture, but through a persistent effort to forge connections—an insistence on bringing the world into the interior of the human being, struggling to stretch and expand the dimensions of the self.

◆ Hou Hsiao‑hsien’s The Puppetmaster (1993)

Hou Hsiao‑hsien’s cinema of the 1990s sustains and reinvents reality in a manner distinct from his contemporaries. Unlike Edward Yang’s precisely choreographed lens that compresses historical complexity, or Ang Lee’s fluid narrative structures that mediate social and familial conflict, Hou’s long, unhurried takes are not about temporal breadth but emotional depth—the subtle, almost imperceptible movement of human feeling. In The Puppetmaster, the biographical story of puppeteer Li Tien‑lu becomes a meditation on fate, memory, and survival. Through static frames, elliptical narration, and the tension between recollection and reenactment, Hou constructs what might be called an “aesthetics of fulfillment,” where each image seems to have already accepted its destiny. I will analyze how the film’s shot composition and script—down to its storyboarded precision—reveal a deep faith in the cyclical rhythm of life and death, transforming realism into transcendence.

◆ Jiang Wen’s In the Heat of the Sun (1994)

"The summer, to me, is a dangerous season," the boy says. "The heat exposes people more than any other time of year—it’s hard to conceal desire." Jiang Wen’s In the Heat of the Sun, adapted from Wang Shuo’s novel Wild Beast, is a disorienting, dazzling portrayal of adolescence in 1970s China. The film’s fractured narration mirrors the boy’s fractured memory—his need for a coherent self colliding with the ideological pressure of a nation rewriting its own past. How can one become a hero without inventing the meaning of one’s life? To enter the film’s dreamlike Beijing, one must decipher both historical allusions and the self’s coded desires. While the novel uses first-person introspection to reveal the boy’s animal instinct, the film’s golden light and saturated colors illuminate the sheen of his sweaty, confused yearning. On the brightest days, wildness becomes not just possible—but inevitable.

◆ Hirokazu Kore-eda’s Maborosi (1995)

From Nobody Knows to Still Walking and Like Asura, Hirokazu Kore-eda has long traced the shadow of death inside the texture of everyday life. But it is in his debut film Maborosi that death is most haunting, not as narrative climax but as atmospheric presence. Unlike his later works, which often make things happen—cleverly constructing meaningful details and dramatic tension—Maborosi quietly insists on letting things happen. Its precision lies not in sharp incisions, but in slow, deliberate accumulation of absence. The wounds it leaves are vast, amorphous, and stretch beyond the edges of consciousness. Through exquisitely composed frames and ellipses in editing, the film uses the visible to cradle the invisible, and finds in silence and blankness a reverence for what cannot be named. Drawing from Teru Miyamoto’s novel of the same name, this session will explore how both the author and Kore-eda approach death—not as a break from life, but as its echoing interior.

◆ Hong Sang-soo’s The Day a Pig Fell into the Well (1996)

When asked by a French journalist why he’s so concerned with failed communication, Hong Sang-soo replied, “I can only respond to what is given to me with the utmost innocence.” Asked again about his future plans, he reiterated the same sentence: “I can only respond to what is given to me with the utmost innocence.” This notion of innocence—stubborn, disarming, almost absurd—captures something essential about The Day a Pig Fell into the Well, Hong’s debut feature. While media headlines often reduce his name to “scandal” or “infidelity,” this very term becomes an unvarnished lens for entering his cinematic ethos: an aesthetics of un-beauty, of restrained forms that reject passion’s flourish yet expose drama’s slow ache. Hong films intimacy not to redeem it, but to disillusion it—to reveal how closeness breeds disappointment. The “utmost innocence” manifests not only in his unpolished visual grammar, but more deeply in his relentless, unflinching gaze at human frailty. He doesn’t ask us to sympathize—only to see.

◆ Takeshi Kitano’s Hana-bi (1997)

Let’s begin with a long shot: What major events unfolded in 1997? Then, a medium shot: What kinds of films emerged across Asia that year, and what cultural atmospheres did they reflect? Finally, a close-up: Takeshi Kitano’s Hana-bi. Before entering an aesthetic analysis, we must confront a central question—how should we view cruelty and violence in cinema? Can violence be considered an aesthetic? Why did Japanese audiences and international festivals alike embrace the violence in Kitano’s films? Once we clarify our stance toward suffering and our interpretive position, we can then examine Hana-bi's emotional landscape and the audiovisual logic behind its storytelling. What worldview is revealed through the paintings that appear in the film—artworks created by Kitano himself? He once said, “If I had to name one person who truly shaped my life, it would be my father—he was a house painter.”

◆ Tsai Ming-liang’s The Hole (1998)

Tsai Ming-liang once said, “The greatest function of my films is to become the moon in the sky, or a flower on the ground. When you look at the moon or a flower, you don’t try to understand it, nor seek revelation or knowledge. I want to bring the act of ‘seeing’ back into cinematic thinking.” I will first explore the creative context, performance structure, and symbolic ending of Tsai’s 1983 stage play The Closet in the Room, which he wrote, directed, and acted in. How does this play dialogue with The Hole, especially in its exploration of the tension between solitude and fantasy? Then we’ll closely examine the gender dynamics in The Hole: what kind of relationship unfolds between the two characters, and how do the five Grace Chang musical numbers threading through the film mirror their emotional states and inner desires? How do the musical interludes shift the film’s narrative rhythm? What symbolic force do water, illness, and the literal hole carry throughout the film? What kind of end-of-century prophecy does The Hole offer? And how does Tsai direct his actors—what echoes can we find between his visual art and his filmmaking?

◆ Lee Chang-dong’s Peppermint Candy (1999)

“I want to go back!” The train rushes head-on, yet the narrative moves in reverse. This is a film that begins with death and retraces its steps, backward, toward childhood. Lee Chang-dong uses a train moving in reverse to unravel how a person slowly becomes voiceless and unravels under the overwhelming tide of history. His reversed structure is not a display of technical flair, but an ethical gesture—it forces us to confront the past and to reexamine the roots of collapse. In this film, the train is not merely a vehicle; it is a metaphor for historical pressure and the violent momentum of fate—a blade of time, and a trajectory with no return. The peppermint candy and the act of prayer appear like two trembling nodes in time, suspended between the individual and the era. This session also serves as the conclusion of our exploration of 1990s Asian cinema. From Wong Kar-wai’s Days of Being Wild (1990) to Lee Chang-dong’s Peppermint Candy (1999), we have looked through the eyes of ten directors to witness how history compresses human nature, how it leaves behind its creases, and how cinema opens—again and again—trembling spaces for breath.

Dormant Fire – Six Literary Seminars, Six Cinema Aesthetic Lectures

To treat words and silences with equal care; to treat images with the same reverence as one treats a lens gazing into the void. We read closely, seeking the depth in the smallest gestures, where creators bear both the freedom and peril of expression within the narrowest margins. Look carefully: in an almost motionless state of rupture, narrative structure falters—yet there remain severe, meticulous lines. Look carefully: the creator is writing the nature of fire with a scorched hand. And the dormant fire, as Baudelaire once said, is always being guessed at—it can glow, but it must never burn.

◆ American Literatures in Motion – Six Literary Seminars

One of the deepest shocks I experienced during my graduate studies in the U.S. was encountering how formally intricate and emotionally profound contemporary American literatures are. I long to read them closely, translate them, interview the writers who have dropped explosive force into the literary field in recent years. What do they care about? How do they build worlds? How does every word pull at another? How does white space exert its power? How do rhythm, imagery, and structure reflect a creator’s emotional logic and vision of the world? How do they renew the possibilities of human expression? Each work reveals itself, and teaches us how to read it.

-

Ocean Vuong (Vietnamese American poet) — Time Is a Mother

-

Hannah Lillith Assadi (Palestinian American novelist) — The Stars Are Not Yet Bells

-

Sydney Smith (Canadian picture book artist) — Do You Remember?

-

Valeria Tentoni (Argentine poet) — Anti-Earth

-

Víctor Hugo Díaz (Chilean poet) — A Pure Place

-

Sarah Manguso (American poet and novelist) — Very Cold People

◆ Fault Lines of the Instant – Six Cinema Aesthetic Lectures

At the beginning of every discussion, my first question is always: What moved you? And how did it move you? To answer this, we must examine how the camera moves, how the frame exerts its will, how the editing connects gazes or slices through illusions. What drives the plot forward? Where does the rhythm of narration shift or stall? How does imagery unlock poetic meaning beyond mere events? How can a single line of monologue illuminate all the wrinkles of a life? These questions explore the filmmaker’s worldview and expand our imagination of what it means to be alive.

-

Belgium – Lukas Dhont — Close

-

Ireland – Colm Bairéad — The Quiet Girl

-

Denmark – Jonas Poher Rasmussen — Flee

-

Iceland – Hlynur Pálmason — Godland

-

France – Mia Hansen-Løve — Bergman Island

-

Japan – Ryusuke Hamaguchi — Wheel of Fortune and Fantasy

Must Stand at the Edge: Herzog’s Cinema and The Twilight World

Where does one begin to speak of Werner Herzog?

He once ate his own shoe, hypnotized his actors, and walked toward an erupting volcano. While filming Fitzcarraldo, he led a thousand people to drag a 360-ton steamship over a mountain. In the U.S., he was shot during an interview—he calmly showed the bleeding wound and said, “It’s not significant,” insisting the interview continue and asking others not to chase the shooter. When a close friend fell gravely ill, Herzog walked from snow-covered Munich all the way to Paris—three weeks on foot—believing, “If I walk to her, she will live.” She lived to ninety, blind and unable to walk. She once told Herzog, “This spell is still working on me. It won’t let me die. But I’m tired of life. Now is a good time for me to go.” Herzog replied, “Very well. I declare the spell is lifted.” Three weeks later, she passed away peacefully.

Rather than speak of Herzog’s madness, we should ask: what ecstatic flashes is he chasing? What beauty and terror compel him to live at the edge?

Herzog once said: “My duty is to create poetry. I want to intervene. I want to shape and sculpt. I want to choreograph, disrupt, and fabricate. Filmmaking is always about one thing: searching for a new grammar of images... The definition of man is forged in the act of struggle. Every film I make seeks to transcend factual truth and reveal an ecstatic truth that awakens the audience.” Looking back over sixty years of his work—through countless images and through his novel The Twilight World—Herzog has ceaselessly pursued the same kind of hero: one who defies gravity, who flies, who leaps into the void—and then crashes. All his characters belong to one great family. As Herzog said, they have no shadows, they emerge from darkness, and they are marked by misunderstanding and disgrace. They know their rebellion is doomed, yet they act without hesitation, struggling alone with their wounds, preserving a spotless dignity.

In this lecture, I’ll begin with the chaos that Herzog’s work first brought me as a viewer. In Ancient Greek, chaos meant vast emptiness, or a cleft in space. I want to explore how Herzog’s cinema creates poetic space within that void—how an event born from nothingness can become a heroic act torn from eternity. I’ll discuss my favorite Herzog works, arranged chronologically, spanning feature films, documentaries, essays, and novels: beginning with his 1968 debut Signs of Life, followed by Fata Morgana, Aguirre, the Wrath of God, Of Walking in Ice: Munich–Paris Diary, Heart of Glass, Nosferatu the Vampyre, Fitzcarraldo, Little Dieter Needs to Fly, My Best Fiend, Grizzly Man, The Last of the Unexplored Tribes, Encounters at the End of the World, Meeting Gorbachev, Nomad: In the Footsteps of Bruce Chatwin, Into the Inferno, The Twilight World, The Fire Within: A Requiem for Katia and Maurice Krafft, and his 2023 memoir Every Man for Himself and God Against All.

I Was Never Loved, Which Meant I Had Loved—The Polyphonic Aesthetics of American Poet Louise Glück

Sentences drift. They have no time left.

The first time I truly read Glück was while studying for the TOEFL. I picked up her poems hoping to catch my breath. But ignorance is often the reason I fall into an abyss. How could one possibly breathe with her work? Each of her words extends infinite claws, shaking open a vast emotional space. Astounding. Her language and imagery seem to strike back—not with sentimentality, but in direct confrontation with death’s approach. That eerie, razor-sharp rhythm, the sudden hesitations, and the long breaths—all of it expands the narrative gaze toward a greater danger: a transformative consciousness.

As I read, I found myself crushed by her power to both condense and disperse. I could not stop—one poem after another, I read compulsively. In her poems, the rupture of continuity is just as beautiful as the creativity that mends it. She tries to polish—but the dust has not yet burst from the surface. What remains is the shadow of the hand that wipes. She once said:

“The dream of art is not to assert what is already known, but to illuminate what is hidden.”

In this online reading session, I want to closely examine several poems: First Memory, The Untrustworthy Speaker, The Wild Iris, The Drowned Children, Denial of Death, and her 2020 Nobel Prize speech. I’ll explore how Glück builds a scene around fragility and solitude. How she uses precision to conjure a blurred mystique. How she crafts polyphonic tones to construct a narrative frame—unfolding spirals of emotion and thought.

The Hesitation and Reverence of Speech — A Peter Handke Reading Circle

The limits of my language mean the limits of my world. I used to be drawn to Wim Wenders’ early films—The Goalie’s Anxiety at the Penalty Kick, Alice in the Cities, Wrong Move, and Wings of Desire. But later, when I read Peter Handke’s poetry, novels, and plays, I began to wonder: perhaps what I had loved all along wasn’t Wenders, but Handke.

When did Handke realize he was a writer? He said: “It was June 1963. I was 21. Pope John XXIII was dying. And I thought: ‘Now you’ve broken free of the vortex of expression.’ It was a calm sentence, and at the same time, a trembling one.” In this reading circle, I want to discuss several texts: his 1966 play Offending the Audience, the 1986 poem Duration, the 1987 poem Song of the Child, his 1997 novel In a Dark Night I Left My Silent House, and his 2019 Nobel Prize acceptance speech.

Beyond examining those “calm and trembling” sentences and how Handke weaves them into a poetics—how he intricately orchestrates darkness, layering its depths so that when darkness unfolds, light feels insignificant—I want to delve into the peculiar weight of his voice: weary monologues, intimate confessions, and severe introspections. His seemingly scattered, derailed language drifts—but each word carries a necessary gravity.

What I encounter in his writing is not the thing itself, but its telling. Handke demonstrates a kind of consciousness that experiences a story not to resolve the contradictions of language, but to reveal the contradictions that language carries within existence. As he says in his Nobel speech: “As always, we approach the source. Perhaps the wilderness is no longer there, but what remains wild, ever new, will continue to be: time.”

Interpret Nothing That Isn’t an Extension of the Whole — Cinema & Poetry Salons

A new harmony often emerges from fragmentation. Every contour exists to expose the emotion of the flesh — and that emotion, in turn, is knotted with the mind’s search for meaning. This is what I learned when I first studied poetry at the age of twenty, through Rodin’s sculptures. Yesterday, I took Xiao-Chuan to the Rodin Museum. Standing before several statues of Victor Hugo, I asked him: What do you feel? What gives you that feeling? We looked closely — what did Rodin emphasize in each figure? What slanted into exposure, and what was deliberately hidden? Ultimately, we were tracing how our sensations were activated by specific forms.

Just like every time we enter a film discussion, my first question is always: “What moved you? And how did it move you?” We could, of course, talk about how the camera moves, how the frame asserts its will, how the editing links your gaze or slices through your illusions, what ignites the engine of the plot, where the rhythm of narration shifts or suspends, how a single line of monologue illuminates every crease in a character’s soul…But aren’t all these inquiries meant to press closer to our feelings — to investigate where they come from? What captures us, exactly? Why do we become so intimately entangled with that person — those people — in the film?

These past few days, I’ve been drifting through Paris, shaping this series of ten online Cinema & Poetry Salons, focusing on Cannes Film Festival competition and award-winning films. I want to return to them, to draw near once again. Together with you, I want to practice seeing down to the smallest details while still grasping the architecture of the whole — tracing each creator’s spiritual consciousness, and our own modes of being in the world. As for the limits of interpretation, I always follow what Rodin once said: “Interpret nothing that isn’t an extension of the whole, do not stop at the surface."

◆ Session 1

Film New Zealand: Jane Campion’s The Piano

Poem India: Sridala Swami, “Not Lost but Remains”

This film is not about a woman learning to speak, but about the freedom to refuse to speak. Jane Campion gives us a silent protagonist, yet lets her piano and body resound. Language retreats; sound and desire entwine. The piano is not merely an instrument, but a vessel for love, language, boundaries, and emotional exchange. She uses touch as syntax, silence as will, drawing us close to emotional tremors through wordless gazes. We will discuss: When language ceases to be the primary medium of communication, what becomes the intermediary of body and emotion? Why do images of water, muddy grounds, and submerged landscapes recur? This is both an awakening of a woman’s inner voice and a dialectic of how desire forms structure. Campion shows us—silence is the ultimate voice.

◆ Session 2

Film Norway: Joachim Trier’s Louder Than Bombs

Poem Belgium: Paul Demets, “Better with Light”

Louder Than Bombs centers around a family reunion three years after a mother’s suicide. Through the eyes of three men—father, elder son, and a still-young son—the film maps a tangled recollection of love and misunderstanding. Its editing isn’t just temporal reordering but a simulation of the mind. Nonlinear, fragmented, and full of dissonance between image and dialogue, it approaches the fractured, uncertain truth of memory—always incomplete, yet profoundly real. We will explore: Can cinema, when entering the realm of memory, bypass narrative to touch the unspeakable? If memory can never be “replayed,” can film instead create new memory?

◆ Session 3

Film France: Robin Campillo’s BPM

Poem Turkey: Gonca Ozmen, “Knowingly Guilty”

BPM is about how collective bodies clash, resonate, and resist. With near-documentary visuals, it immerses us in the early '90s AIDS activist group in France, showing how youth, on the brink of losing speech, find fierce ways to vocalize. The film juxtaposes floating dust in light—particles unfiltered by failing immune systems—with intense physical presence: dance and cries versus fading stillness. These “dust moments” are metaphors not only for death, but for the fluid state of love. The film isn't just historical recreation, but a formal reconstruction of memory: politics as emotional architecture, and love as the last ethics in extremis.

◆ Session 4

Film UK: Yorgos Lanthimos’ The Killing of a Sacred Deer

Poem USA: C.D. Wright, “The Gardener”

This film continues Lanthimos's exploration of ethical dilemmas within absurd orders. Through a mythic punishment ritual overlaid on a modern family, it offers a cold-eyed scrutiny of free will and civilization. A doctor must sacrifice a family member to lift a curse stemming from past error. The camera surveys interiors and bodies with detachment, the sound design is emotionally muted, and dialogue robotic, as if all feelings are frozen beneath an icy surface. The violence here lies not in gore but in its atheist gaze: relentless, judging cowardice and collapse. The title evokes Greek myth, casting the film as a modern fable—absurdity meets absurdity, suppressed guilt returns in eerie form.

◆ Session 5

Film USA: Jim Jarmusch’s Paterson

Poem All poems written by the character Paterson in the film

In Paterson, Jarmusch returns to themes of solitude, poetics of the everyday, and static time. His protagonist embodies a marginal serenity, refusing drama, living in stillness. He wakes, works, listens, returns home, talks with his wife, walks the dog, has a drink, writes again. The film spans a week, with near-identical days, like life’s photocopy. But through repetition, we begin to see what is usually unseen: shifts in light, fractures in dialogue, turns in poems, emotional drift. Tiny deviations become poetic fissures. Jarmusch replaces drama with quietude, order against chaos, denying climax in favor of "form in being itself," guiding us into a dormant, stirring creative state.

◆ Session 6

Film Russia: Andrey Zvyagintsev’s Loveless

Poem Netherlands: Eva Gerlach, “Story”

Interviewed by an American journalist, Zvyagintsev said the English title Loveless was inaccurate. The Russian Нелюбовь means anti-love—not a lack, but the opposite of love. His lush compositions and smooth edits expose Russia's contemporary cruelty. In this world, reconciliation is impossible without replacing reality itself. Asked about “slow cinema,” he said: “Slowness is not a method. It doesn't soothe or flatter, but builds trust. Its aim isn't the story, but the unveiling. It demands the audience trust and do their inner work.” We will examine: What do we see in Zvyagintsev’s long takes? How is the veil lifted? Why is this a film about the opposite of love?

◆ Session 7

Film Korea: Lee Chang-dong’s Burning

Poem Korea: Kim Il-deok, “Retro Soul”

In Murakami Haruki’s "Barn Burning," it’s the finger snap that matters. In Lee Chang-dong’s Burning, it’s the man staring into a dim room lit for a fleeting moment by tower-reflected light during sex. Between disappearance and metaphor, Murakami asks us to follow sound; Lee, to track light and shadow. Our urge to name ambiguity equals our urge to frame. The point isn't what it is, but what we believe it could be. Facing uncertainty becomes an inner force for class-resisters, and a reason for writers to write: once seen, ambiguity can be navigated. Even if unconscious, clarity stems from how we read the blur, where we place it, and where our gaze follows.

◆ Session 8

Film Italy: Alice Rohrwacher’s Happy as Lazzaro

Poem Netherlands: Saskia de Coster, “I Put on My Species”

Rohrwacher's films are about miracles. Her debut Corpo Celeste ends with, "Want to see a miracle?" The Wonders was originally titled Miracle. Happy as Lazzaro shows a literal miracle. In Her Eyes captures childhood magic, while La Chimera centers on unearthing lost civilizations. Each begins with a group scene in darkness: people bound by old rules, unaware of their blindness, until a protagonist pierces through. Miracles aren’t gradual awakenings, but unveil a religious core of life: open to all, unfiltered, absurdly innocent, sacred to the point of revolution. Beauty and goodness may not protect the protagonist, but creating one's own faith and living by it becomes the only escape. The fool-saint’s blindness lies in ignoring all boundaries.

◆ Session 9

Film Sweden: Ali Abbasi’s Border

Poem Kazakhstan: Aigerim Tazhi, “And You Were There”

Border is a mythic parable and a poem on liminality and belonging. It avoids rushing to reveal, instead following bodily metaphors slowly. It abandons human perspective, inviting us to see “humanness” through other eyes. Shot in moist, somber Nordic forests and grey lakes, it crafts an eerie, hybrid habitat. Sound and gestures convey pre-linguistic animality, unsettling yet deeply moving. As the film explores sex, wildness, and historical trauma, we realize: it's not about humans becoming monsters, but a return to origins—a revolt against discipline and civilization. We will explore how this “intimate strangeness of belonging” challenges our notions of family, love, and body. When intimacy surpasses the human, when strangeness is native, are we closer to our forgotten, true self?

◆ Session 10

Film France: Céline Sciamma’s Portrait of a Lady on Fire

Poem USA: E.E. Cummings, “somewhere i have never travelled”

The gravity of love arises from absence. The power dynamics of intimacy invent a shifting dance of closeness and retreat. Our possibilities emerge through mutual recognition—alongside death and liberation. I will examine Portrait of a Lady on Fire as a reenactment of love: how "creation" relates to the lover, the painting, and a mode of existence. I will also trace how Sciamma, from Water Lilies to Tomboy, Girlhood, Portrait, and Petite Maman, composes emotional scores, gazes at the limited to evoke the possible, and paces her films with slow simmering, not plot urgency, but an immersion in nothing-happens time to catch internal shifts. How does she conjure such intimate, tense, and sensuous interior cinema?

.jpg)

When Egg Whites Meet Heat — Six Poetry Sessions, Six Film-Image Salons

How does distance come near?—This question has surfaced in my mind upon waking these past few days. Not a question, really, but a marvel. I still remember the earliest moment of wishing, etched deeply within a vast, unformed blank. I knew nothing, and yet it was perfectly clear. I knew nothing, and therefore that clarity was simply the intensity of my projected longing. What had I gone through to get here? Looking back now is as blurry as looking forward then. And yet, I am now in the place I once wished to be.

It is Bergman’s island, Pessoa’s Lisbon, Ozu’s grave, Kitano’s ocean, Picasso’s Antibes, Wong Kar-wai’s Grand Clock, escalators, and Goldfinch Restaurant. I will soon head to Turkey to learn the Sufi whirling, a wish I made twenty years ago after watching Chance or Coincidence. Then there is Rilke’s Swiss Valais, Victor Erice’s Hive House, the ruined monastery in Tarkovsky’s Nostalghia, and the lighthouse that Lai Yiu-fai never reached.

This morning, while frying an egg, I realized that each “after” is simply the visible aftermath of a former “before.” Heat, oil, cracking the shell on the table’s sharp edge, letting the egg slide smoothly into the pan. The transparent egg white flows outward—I lean in, watching transparency turn milky, the milky part firming and spreading. The white does not erase the transparent; the transparent becomes the white.

It was always there—just waiting to be developed. In this light, my life seems a nearly boringly simple mechanism: before, I make a wish; after, I live into that wish. Again and again, repeated. When I fall in love, I plunge into their world with abandon—feast or ash, I claim it all. Uselessly, I move toward light. Whatever slices them open, slices me too.

My boundless passion lies in tracing their before and after—understanding what struck them into forging their miniature universes.

Transparent egg whites, when exposed to heat, have no choice but to whiten and set. Love drives my every “after.” The poems I introduce in the Poetry Sessions are contemporary American works that have pierced me with their expressive form. The films I select for the Film-Image Salons are old European films that electrify me—I tremble before them, obsessed and undone. We will practice looking—again and again, directly and without residue—as if seeing text, symbol, and image for the first time, so much so that we cannot help but trace their contours in our minds. Then, every work that appears before us will slowly unveil itself, teaching us how to read it. Not rushing to project what we already know, not rejecting the work’s attempt to speak to us in new, blurred languages. Poetry and cinema are like translucent egg whites—when touched by our pure flame, they slowly reveal themselves, emitting a color and scent we have never encountered. Their setting solidifies us—by first breaking us.

And when broken, what lies inside? I curate these Poetry Sessions and Film-Image Salons to bring you back to an unwritten state of falling in love: when your willingness to listen is so vast that you no longer recognize yourself. You did not know you had such power to move yourself. Called forth, awakened—in this loosening, you unexpectedly meet a version of yourself you never knew. Transparent, flowing, poised to become—I long for my classes and salons to return you to that tender, unwritten state of love, not only between you and a work, but between you and yourself. To fall into the chaos where old structures collapse and new orders have not yet formed. You too are the egg white meeting heat—meaningless, yes, but covered by something greater than yourself, slowly feeling out your own eyes and nose.

When we, poetry, and cinema all meet the heat—distance arrives, intimately, as near.

◆ Contemporary Poets of the Americas — Six Poetry Reading Sessions

I’ve chosen six poets from across the Americas whose works have profoundly moved me, and translated their poems personally. Before each session, we will read three to five poems by the featured poet; during class, we’ll explore and discuss the unique aesthetics through which they express emotion and construct their worlds.

Session 1 – Colombian poet Lucía Estrada

Session 2 – Mexican poet Rocío Cerón

Session 3 – Iraqi-American poet Dunya Mikhail

Session 4 – Dominican poet Frank Báez

Session 5 – American poet Eileen Myles

Session 6 – Alaskan poet Abigail Chabitnoy

◆ Old Films of Europe — Six “Cinema & Poetry” Salons

Drifting, improvising, lingering in sunken places. We’ll closely examine each film, tracing the hooks that stir our emotions—how does the film exert its force? What does it reel in? Each salon concludes with a reading of a poem I’ve selected to resonate with the film, expanding our field of vision and imagination.

Salon 1

film: Persona – Ingmar Bergman, Sweden

poem: “Windows and Doors” – Farhad Showghi, Germany

Salon 2

film: L’Avventura – Michelangelo Antonioni, Italy

poem: “Portrait” – Mary O’Malley, Ireland

Salon 3

film: La Notte – Michelangelo Antonioni, Italy

poem: “I Remember” – Esther Polak, Netherlands

Salon 4

film: La Dolce Vita – Federico Fellini, Italy

poem: “Elegy with a Closed Mirror” – Trevor Joyce, Ireland

Salon 5

film: All About My Mother – Pedro Almodóvar, Spain

poem: “To the Dearest Stranger” – Ingmar Heytze, Netherlands

Salon 6

film: Talk to Her – Pedro Almodóvar, Spain

poem: “Season of Fire” – Michael Higgins, Ireland

Voices Emerging from the Blank — A Poetry Reading and Writing Course

In 2010, during my very first Butoh class in Japan, Yoshito Ohno handed us Hokusai’s ukiyo-e print The Great Wave off Kanagawa and asked us to observe the smallest details while also seeing the farthest distance. Since then, I’ve read poems—and people—with the same kind of gaze.

What does it truly mean to have a dialogue with a poem? How do we look directly and incisively? How do we grasp the reverberating meanings in the call and response? How do we follow each word and blank space toward another soul? How can a poem renew our ways of sensing and imagining life?

I’ve chosen ten contemporary women poets from the Americas whose works deeply moved me, and translated their poems into Chinese, attempting to preserve their unique expressions of emotion and world-making. In this ten-session online course of “Poetry Reading and Writing,” we’ll closely read three poems by one poet each session, followed by improvisational writing in class, training our eyes to see both the details and the distant whole.

◆ Session 1: Native American Poet Layli Long Soldier

Even the smallest wild grass carries the force to strike emptiness. Layli’s most exquisite craft lies in how she uses silence and blankness to strike. She loops and inverts a single image or syntax through multiple layers—lyrical and sharp—each word tightening the gears of the poem. Her vehicle crashes head-on into America’s systemic violence and cultural erasure of Indigenous people.

◆ Session 2: Iranian-American Poet Solmaz Sharif

Solmaz examines how military language infiltrates the everyday—and how the everyday mirrors violence and war. She explores how facts, history, and truth are constructed in language. How does the language of power premeditate violence against the body? Where lies the legitimacy of America’s intervention in the Middle East? Though Solmaz cannot resist death and loss, she resists the language of war-makers, using humanized detail to defy the hollow rhetoric of violence.

◆ Session 3: African American Poet Destiny O. Birdsong

Destiny writes the body, and the body being looked at. There is the touch of power, the continuation of violence, the blurred lines of desire. She brings language close to the skin, where feeling is peeled open and new perceptions grow from pain. She does not write from a posture of accusation, but lets trauma become a point of insight, redefining the weight of “freedom” with every breath.

◆ Session 4: Inuit Poet dg nanouk okpik

dg once said, “In the Inuit language, there is no ‘I.’ Humans are interconnected with all forms of life.” With the same eyes, she watches a southern white eagle arrive in Arctic skies, observes glaciers’ beauty and melting, sees sun-cracked Inuit women and kids playing video games. dg perceives as a human but without the human urge to dominate; she lives through the human body yet transcends limited cognition to witness a larger world.

◆ Session 5: Asian American Poet Victoria Chang

Victoria Chang begins from the most ordinary of objects—their appearance, sound, texture, and taste. Just when we are about to truly sense them, they disappear. What we suddenly hold is a space of perception and memory constructed by her five-sense rendering of that simple object—a new entity. Its disappearance doesn’t defeat us; rather, the emerging poetic moment grips us breathless.

◆ Session 6: Vietnamese American Poet Nguyen

To continue life by holding the broken. Diana doesn’t approach her late brother through fragmentation itself, but through the grammar of relationships between him and the rest of the family. Between presence and absence, between voice and silence, Diana implants her radical empathy, while preserving the inevitable gap that honors the impossibility of “becoming the brother.”

◆ Session 7: Canadian Poet Chelsea Dingman

Chelsea Dingman’s rapidly shifting thoughts create seismic rhythms in her poems—not musicality of sound, but musicality of thought. If we can keep up with the flow and twists of her thinking, we’ll connect each point she excavates through leaps. Her way of holding the self is to dissolve it—settling her stubborn obsessions in the swing of contradiction.

◆ Session 8: Mexican Trans Poet Fei Hernandez

Fei’s poetry is a continual spell of transformation. Language flows through their body like water, resisting fixed gender or identity. Each poem is a ritual of bodily rebirth—spoken in Spanish, English, prayers, or tones of lightning—transmuting pain into energy. Fei does not seek to be named, but to summon the untranslatable. Poetry becomes a politics of breathing, a space where the self coexists with ancestral spirits.

◆ Session 9: Alaskan Native Poet Joan Naviyuk Kane

Joan’s poems are cracks in the ice field—cold, yet crystal clear. Interweaving Alaskan Indigenous vocabulary with English, she writes of vanishing lands, peoples, and mothers. Her short lines are like stone patterns carved by the wind—silent, but filled with the voice of memory. She returns language to its origins—both a landscape and a soul’s root—redefining what it means to “go home” between isolation and connection.

◆ Session 10: American Poet Jorie Graham

Jorie’s poems are structurally complex, weaving long lines into irregular rhythms. She makes rich use of distinctive sentence patterns and diction to create layered language. Her style ranges from crisp to intricate and shifting, touching beauty and destruction, the mechanics of existence, the edge of language, the boundaries of poetry. She guides us into a journey of philosophical meditation.