Death Is Dying

Author: Yu-Hsuan Wu

Publisher: Self-published

Year: 2021

Language: Bilingual (Chinese-English)

Pages: 40

ISBN: 978-957-43829-6-5

【About the Book】

What is death? How did it enter a mother’s body? How did it begin to blanket her daily life? As a daughter, how does Yu-Hsuan Wu confront death face to face? How does she endure its call?

In Death Is Dying, Wu writes: “This small book documents the final days before my mother’s death. As I held my breath and tracked the traces of death, my mother’s outline became increasingly clear to me. Death illuminated the full shape of the dying woman. When I finally saw the will that carried her life, death began to vanish.”

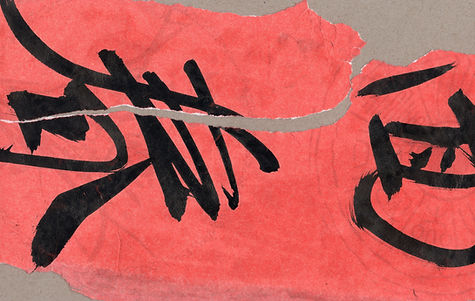

According to Taiwanese tradition, red spring couplets—symbols of joy and celebration—must be torn down from a home the moment someone passes away. On the morning her mother died, Wu tore down the red paper from their front door and used it as the cover of this photographic notebook—sealing time and memory within it, giving death its own eternal flesh.

【Selected Works】

Rupture

“Should we kneel?” Without consulting anyone, I said yes. We would kneel. It was me—I was the one who desperately needed this final moment. To face your body with the response of my own.

Before you died, a pink rupture appeared in the crease of your buttocks. A rupture—tender, raw flesh. I picked up a cotton swab, dipped it in saline, and gently wiped it clean. You remained motionless. Ever since you had moved from your upstairs bedroom, where you had slept for over thirty years, down to the study, and then from the study to the living room—since you had sat on the commode in that living room, pulling down your underwear to release everything private, everything dignified—you had stopped moving. You used what little strength you had left to maintain the shape of a person.

A joyous wedding ceremony, in the end, is still a disheveled performance. Only this final kneeling felt real. I knelt before you, unmoving, remembering how I had defied every simple expectation you had for me. I could not speak. My tears washed away my makeup. Only now do I realize—the white veil draped across my forehead was meant to conceal the rupture. When I understood that the weight pressing upon my knees was the same weight you had shouldered all your life, I wished I could kneel forever—to hold onto your gaze piercing through my white veil.

At the crematorium, I knelt, unable to find a place to set down my grief. Then, my nephew cried out in a sharp, desperate voice: “The fire is coming, run!” His voice was full of anguish, yet he had no choice but to push past his own small sorrow, terrified that the fire would burn you. So he screamed with all his might. He roared the truth into the air—and suddenly, the ritual came alive. In that moment of calling out, I finally allowed myself to enter.

I am too fragile. I always need something pure to break me open. Just like when I was nineteen, and you drove from Taitung to Tainan to see me. I took you to the library, where a small television was playing Chance or Coincidence. I didn’t know what to say to you—only that I wanted to watch my favorite film with you. In it, the woman moves toward death as she lives, and when she understands that God exists only in the eyes of the ones we love, the screen flashes black for an instant—and you and I, we were reflected in that dark mirror.

One early morning when I was ten, I started bleeding. I didn’t know what to do, so I folded thick layers of tissue into my underwear and sat still, playing the piano all day. Only when you came home that night did I finally tell you my secret. From that day on, if my bleeding secrets were not told to you, then they would never be told to anyone.

【Cross-Media Expressions】

In 2023, during Yu-Hsuan's artist residency in the medieval town of Noyers-sur-Serein, France, she chose to perform Butoh in an abandoned public washhouse. She thought, "For centuries, women came to this place to scrub away the dirt from their laundry. What is it that I came to wash? Can it even be washed away? Using North African herbs, I inscribed lines of poetry—written for my mother—onto my skin. I wore my relationship with her on my body; the poems became a second layer of skin. In the past, I wanted to rid myself of everything my mother had given me—I did not wish to inherit her dust. But now, as my sense of self dissolves, I am able to coexist with the body she gave me, and I can feel the invisible imprint of her love."